Git's guts: Branches, HEAD, and fast-forwards

Lets get some learning done. There are a few questions that keep cropping up when I introduce people to Git, so I thought I’d post some answers as a mini-series of blog posts. I’ll cover some fundamentals, while trying not to retread too much ground that the fantastic Git community book already covers so well. Instead I’m going to talk about things that should help you understand what you and Git are doing day-to-day.

What’s a branch?

I know what you’re thinking. “C’mon, we know what a branch is”. A branch is a copy of a source tree, that’s maintained separately from it’s parent; that’s what we perceive a branch to be, and that’s how we’re used to dealing with them. Sometimes they’re physical copies (VSS and TFS), other times they’re lightweight copies (SVN), but they’re copies non-the-less. Or are they?

Lets look at it a different way. The Git way.

Git works a little differently than most other version control systems. It doesn’t store changes using delta encoding, where complete files are built up by stacking differences contained in each commit. Instead, in Git each commit stores a snapshot of how the repository looked when the commit occurred; a commit also contains a bit of meta-data, author, date, but more importantly a reference to the parent of the commit (the previous commit, usually).

That’s a bit weird, I know, but bare with me.

So what is a branch? Nothing more than a pointer to a commit (with a name). There’s nothing physical about it, nothing is created, moved, copied, nothing. A branch contains no history, and has no idea of what it consists of beyond the reference to a single commit.

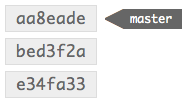

Given a stack of commits:

The branch references the newest commit. If you were to make another commit in this branch, the branch’s reference would be updated to point at the new commit.

The history is built up by recursing over the commits through each’s parent.

What’s HEAD?

Now that you know what a branch is, this one is easy. HEAD is a reference to the latest commit in the branch you’re in.

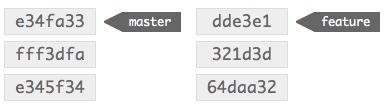

Given these two branches:

If you had master checked out, HEAD would reference e34fa33, the exact same commit that the master branch itself references. If you had feature checked out, HEAD would reference dde3e1. With that in mind, as both HEAD and a branch is just a reference to a commit, it is sometimes said that HEAD points to the current branch you’re on; while this is not strictly true, in most circumstances it’s close enough.

What’s a fast-forward?

A fast-forward is what Git does when you merge or rebase against a branch that is simply ahead the one you have checked-out.

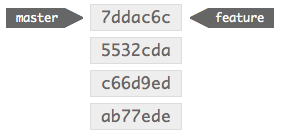

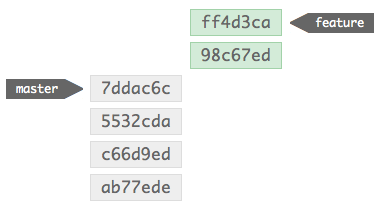

Given the following branch setup:

You’ve got both branches referencing the same commit. They’ve both got exactly the same history. Now commit something to feature.

The master branch is still referencing 7ddac6c, while feature has advanced by two commits. The feature branch can now be considered ahead of master.

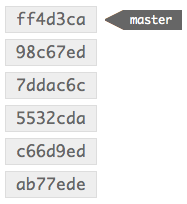

It’s now quite easy to see what’ll happen when Git does a fast-forward. It simply updates the master branch to reference the same commit that feature does. No changes are made to the repository itself, as the commits from feature already contain all the necessary changes.

Your repository history would now look like this:

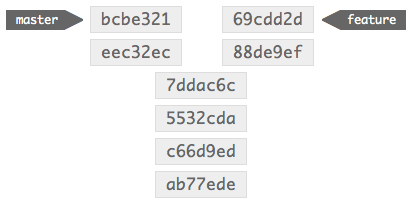

When doesn’t a fast-forward happen?

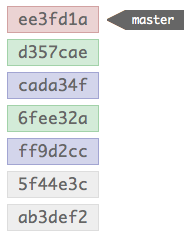

Fast-forwards don’t happen in situations where changes have been made in the original branch and the new branch.

If you were to merge or rebase feature onto master, Git would be unable to do a fast-forward because the trees have both diverged. Considering Git commits are immutable, there’s no way for Git to get the commits from feature into master without changing their parent references.

For more info on all this object malarky, I’d recommend reading the Git community book.